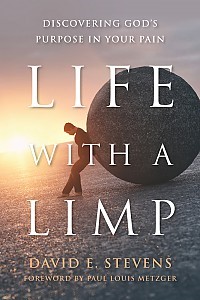

Paraclete associate David Stevens has traveled the world with his wife, Mary Alice, pastoring and training pastors. In his latest book, “Life with a Limp: Discovering God’s Purpose in Your Pain,” he journeys with readers through the difficult topic of suffering. He shares his firsthand experience of losing a son, wrestling with God and growing through grief. In 2004, his son, Jonathan, died from carbon monoxide poisoning while staying at a hotel in Korea.

Paraclete associate David Stevens has traveled the world with his wife, Mary Alice, pastoring and training pastors. In his latest book, “Life with a Limp: Discovering God’s Purpose in Your Pain,” he journeys with readers through the difficult topic of suffering. He shares his firsthand experience of losing a son, wrestling with God and growing through grief. In 2004, his son, Jonathan, died from carbon monoxide poisoning while staying at a hotel in Korea.

Paraclete writer Rebecca Hopkins sat down with David to talk about his book.

Let’s start with describing what your message in the book is.

The book grew out of our experience of loss of our firstborn, Jonathan. But that loss obviously brought to the surface—as catastrophic loss often does in our lives—other experiences of loss. Whenever we go through suffering, pain, or loss, it brings with it, sort of like a tsunami, other issues that are under the waterline, so to speak. And so that’s difficult but also a great opportunity because it enables us to go back and better understand some of the other suffering, pain, and emotional hurt that we’ve been through in life. And it obviously provokes a lot of personal inventory and self-evaluation.

The book is about suffering. It basically is about walking through suffering, and growing through suffering, and these form the two main parts of the book.

The first four chapters are devoted to how to walk through suffering. And the last five chapters are devoted to how to grow through suffering. And then inserted right in the middle of the book is an interlude, Jacob at the Jabbok, which is the story of Jacob, with the “Hound of Heaven” on his heels, bringing him to a point of greater brokenness in his life so that he could more fully embrace God’s blessing in life.

Looking back at your experience, what did you need at that time? And what do people need when they’re in the suffering? How can we come alongside them well?

One thing we must NOT do is we must not offer stock and trade answers, like, “God intended this to build your character,” or “Providence writes straight with crooked lines.” Such cliches sometimes might (have) a of kernel of truth, and yet there’s actually a lot of distortion of truth.

I believe that they need to know that Christ cares, that Christ listens, and that only really in our tears, can we best see His tears. God has emotion. Christ has emotion, and it’s the pain and suffering of Christ that best enables us to walk through suffering in our own lives.

In fact, one of the main ideas developed in the first part of the book is that we must allow our l imp in life to move us to contemplate the cross of Christ. It’s at the cross of Christ that we find not only the answer to the issues of evil and suffering, but also are reminded of His identification with us in our suffering.

imp in life to move us to contemplate the cross of Christ. It’s at the cross of Christ that we find not only the answer to the issues of evil and suffering, but also are reminded of His identification with us in our suffering.

And then thirdly, we need to be the hands and feet of that in the lives of people. We must have a listening ear, walking alongside people, just sitting and being available to cry, to weep, to be present.

When we first got the word about Jonathan’s death, one of my associate pastors came. We had just gotten a call from the US Embassy in Seoul, Korea. Mary Alice had received the call. When I arrived at the house, she told me that Jonathan had died and was with the Lord. You just need people that sit and listen—I think our associate pastor really did an amazing job. He just came in and held me. He sat with us and cried and listened.

Wow. Thanks for sharing that.

Of course, that’s on the emotional side. You know, we’re spiritual beings. We’re emotional beings. We’re intellectual beings. We’re psychological beings. Eventually, the more philosophical questions press in on the mind and on the soul, questions like, “Why did God allow this?” And while suffering afflicts the body, the problem of suffering afflicts the mind. And the problem of suffering eventually will begin to weigh on the human soul. So, at the appropriate time, we need some answers.

So chapters two and three are rather apologetic in nature because when it comes to suffering and pain, one of the greatest obstacles to people believing in God is that they attribute to God the fault for their suffering. As we move through suffering, we need to be able to express our emotions, even emotions of anger. But actually anger at God reflects a worldview. It reflects a certain view of God’s sovereignty. If God meticulously, in an omni-controlling way, exercises His sovereignty over everything by control, then He is ultimately responsible for the pain and the evil in the world.

As to the tension of God’s sovereignty and human suffering, I place the onus on the back of our adversary, Satan, who is the ultimate schemer behind pain, evil and suffering in the world, not God. And I think only as we begin to adopt more of a warfare view of Scripture, and what I consider to be a more biblical view of God’s sovereignty, will we avoid the tendency to blame God for the pain.

I’m curious…when you have shared either through preaching or even one-on-one your story about Jonathan, does it make others more open to what you’ve learned?

I mentioned in the book that during the initial years after Jonathan’s death, while pastoring Central Bible Church, I often wept as I preached. I sometimes shed tears in the pulpit. And sometimes those tears came very unexpectedly.

I found that sharing honestly and openly was very important for others. It’s become part of our testimony. And I think that’s part of the healing process and pain. We take trouble, and we can, by God’s grace, turn it into testimony. And that testimony is a witness to the importance of lamentation within the body of Christ.

A third of the Psalms are of lament—51 out of 150 Psalms are Psalms of lament. Unfortunately, within the worship of the church, the whole aspect of lament has sometimes been neglected. There’s not enough opportunity for people to appropriately lament and to express their grief and the reality of pain that they experience.

So, I believe that yes, sharing openly and honestly but not inappropriately, can be very helpful in encouraging others to express their lament and to worship even while in pain.

I have my wife sitting right here, and you might like to ask her a question from a woman’s standpoint. Though I wrote it, she read every word and chapter multiple times. And it was an opportunity for us to grow together through the process.

Mary Alice, I’d love to hear your thoughts about this book and what it means for your family and others in your ministry. Does it feel vulnerable to have this story out there?

Actually, no. It feels good for David to be able to explain some of what his own process has been, and it’s important to be able to help others. We’re so connected to so many people and frankly, our prayer life is just overflowing with people to pray for. That’s really been a wonderful thing about the book coming out, knowing that there are a lot of folks that we know personally who are buying it. It’s a great joy to be able to participate in that experience.